Does the language we speak influence how we think, feel and act towards the natural world?

John A. Lucy (1997) - Linguistic Relativity. Annual Review of Anthropology

Few ideas generate as much interest and controversy as the linguistic relativity hypothesis, the proposal that the particular language we speak influences the way we think about reality. The reasons are obvious: If valid it would have widespread implications for understanding psychological and cultural life, for the conduct of research itself, and for public policy.An interesting thread on Twitter popped up last year on the topic of ‘linguistic relativity’ from Tom Pepinsky, a political scientist at Cornell. In a nutshell, linguistic relativity is the idea that the language(s) we speak influences how we think. It suggests that our everyday experience of reality — our worldview — is influenced in either big or small ways by the language we speak. It’s an idea made famous by the linguists Edward Sapir (1884–1939) and his student Benjamin Lee Whorf (1897- 1941), hence the other name for linguistic relativity: ‘the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.’

The idea of ‘linguistic relativity’ has fascinated everyone from psychologists, to sci-fi writers (remember the movie Arrival)?), to the emerging and controversial field of ‘Whorfian economics’ (more on this below).

🎥 Arrival's Linguistic Relativity and Time Perception Are Awesome | Video (5:13 minutes)

“The Story of Your Life” Book: https://www.amazon.com/Stories-Your-Life-Others-Chiang-ebook/dp/B0048EKOP0/

But just to illustrate the idea of linguistic relativity a bit more, Tom gives the famous example of Guugu Yimithirr:

This evidence from Guugu Yimithirr suggests a ‘weak’ version of the linguistic relativity hypothesis: the language we speak influences how we experience the world in very subtle ways. In this case, the enhanced ability of Guugu Yimithirr speakers to ‘dead reckon’.

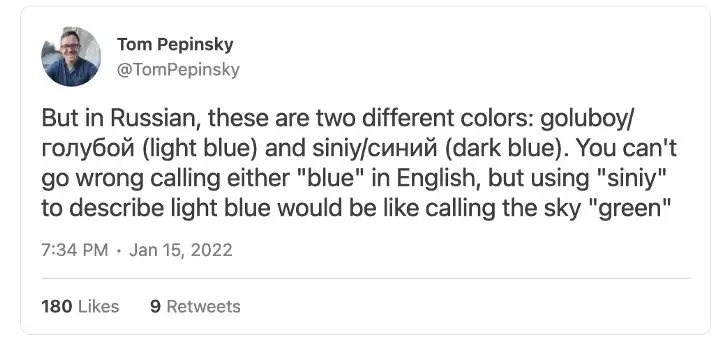

Another example of the ‘weak’ version of linguistic relativity is how Russian speakers are slightly faster at experimental tasks involving blue color classification than English speakers. The linguistic relativity claim here is that the Russian language distinguishes different shades of blue as completely different colors, whereas English speakers just perceive different shades of the same color: blue. Pepinsky also explains this oft-cited finding nicely in his thread:

While these examples illustrate the ‘weak’ version of linguistic relativity, Tom is concerned about a ‘strong’ version of the hypothesis gaining traction in a controversial new subfield of economics he calls ‘Whorfian socioeconomics’. Rather than language just having a subtle influence on our everyday patterns of thought, the ‘strong’ version of the linguistic relativity hypothesis goes something like this:

For example, Whorfian socioeconomists make the stunning claim that people who grow up speaking a ‘futureless language’ (Chinese) save more money than people who speak ‘futured’ languages’. On a side note, in all my linguistics courses, I have never heard of languages being classified in this way, and it seems to exist only in this subfield of economics. One of the leading Whorfian economists, Keith Chen, explains his claim about the difference between futured and futureless languages like this, comparing English (a ‘futured language’) with Mandarin Chinese (a ‘futureless language’) (See Keith’s TED talk here):

🎥 Keith Chen: Could your language affect your ability to save money? | Video (12:13 minutes)

Keith Chen

[Chinese speakers] can say yesterday it rained, now it rained, tomorrow it rained. In some deep sense, Chinese doesn’t divide up the time spectrum in the same way that English forces us to constantly do in order to speak correctly…You speak English, a futured language, and what that means is that every time you discuss the future or any kind of a future event, grammatically, you’re forced to cleave that from the present and treat it as if it’s something viscerally different.Now suppose that that visceral difference makes you suddenly disassociate the future from the present every time you speak. If that’s true, and it makes the future feel like something more distant and more different from the present, that’s going to make it harder to save. If, on the other hand, you speak a futureless language, the present and the future, you speak about them identically. If that suddenly nudges you to feel about them identically, that’s going to make it easier to save.So, for Whorfian economists, it seems a particular language — or more specifically how the dimension of time (tense and aspect) is expressed through a particular language — does not just influence individuals’ thoughts, but determines how whole societies behave. ‘These are BIG claims!’ Tom Pepinsky says:

Tom Pepinsky

What if people with obligatory politeness distinctions [like ‘tu/vous’ in French] in pronouns are more authoritarian than the rest of us? What if people with future oriented languages save more [money] than other people? These are BIG claims! I term this literature “Whorfian socioeconomics.” It’s linguistic relativity for the big leagues. Not just how we think, or how we go about our lives, but how whole societies are oriented. I also think that the evidentiary base for such claims is very thin.The gist of Pepinsky’s thread isn’t that the linguistic relativity hypothesis is wrong. In fact, his Twitter thread points to several areas of research that show how language influences our experience of the world in all sorts of fascinating ways. And I know many other language researchers find linguistic relativity fascinating, me included.

But in his recent article, Pepinsky warns: “I’m going to confess something: I am rooting against Whorfian socioeconomics. I think it is a dangerous position to hold that language matters in this way.” It is a dangerous position because it harkens back to an old colonial idea in Western philosophy that some ‘named languages” are better for thinking, and therefore more advanced than others. As he says, “There are no objectively good or bad languages, or strong or weak languages. Nobody’s thoughts are crippled by the language that they speak.”

I think this is an important point for environmental communication. Does the language(s) we speak influence our environmental worldview? Or, to put it another way, does speaking English as a first language influence my experience of nature differently than say, people who grow up speaking French or Japanese?

For environmental communicators, I want to suggest these are unhelpful questions to ask. Starting with questions about the influence of a ‘named language’ like ‘English,’ ‘French,’ or ‘Mandarin Chinese’ on our patterns of thinking and behavior is where we risk getting into trouble in my view.

Just think of the radical diversity of environmental worldviews expressed by speakers of ‘English,’ or ‘French’ or ‘Japanese.’ Speakers of these languages express and act out a wide spectrum of both anti- and pro-environmental thoughts and behaviors, even though they may be using the ‘same language.’ Not to mention that most people on the planet are multilingual; do they experience conflicting worldviews, or switch between better and worse environmental behaviors when they switch languages?

Rather than the common ‘named languages’ approach, I think a more helpful way of thinking about eco-linguistic relativity — how language influences our environmental thinking and behavior — is a ‘discourse-oriented approach.’

Sociolinguist Joe Comer made this point commenting on Pepinsky’s thread…

Luckily, the field of ecolinguistics gives us a fantastic set of tools for exploring linguistic relativity from a discourse-oriented approach! According to ecolinguist Arran Stibbe, ‘discourses’ are the “standardised ways that particular groups in society use language, images and other forms of representation.” And these standardized ways of using language inform the kinds of ‘stories-we-live-by.’

From this perspective, it’s not the particular language we speak that influences our thoughts and actions, so much as the underlying ecologically destructive or beneficial ‘stories-we-live-by’ we use any language to express. As Stibbe puts it,

To give one last example, Robin Wall Kimmerer eloquently offers a similar ‘story-we-live-by’ approach to understanding eco-linguistic relativity in her fascinating essay: “Speaking of Nature: Finding language that affirms our kinship with the natural world.” Here, she asks about the potential for speakers of any language to resist destructive ecological stories, and how we might come to share more beneficial stories-we-live-by across our linguistic and cultural differences:

Robin Wall Kimmerer

…At Standing Rock, between the ones armed with water cannons and the ones armed with prayer, exist two different languages for the world, and that is where the battle lines are being drawn. Do we treat the earth as if ki is our relative — as if the earth were animated by being — with reciprocity and reverence, or as stuff that we may treat with or without respect, as we choose? The language and worldview of the colonizer are once again in a showdown with the indigenous worldview. Knowing this, the water protectors at Standing Rock were joined by thousands of non-native allies, who also speak with the voice of resistance, who speak for the living world, for the grammar of animacy.