Forget wabi-sabi, ikigai, and kintsugi. This is the one phrase to really understand Japan.

When you study introductory Japanese, you learn a set of daily expressions: konnichi wa, sumimasen, gomen nasai, arigatō…

But there’s one critical expression missing from the introductory textbooks. One expression you not only hear every day, but epitomizes the attitude to life in Japan.

This expression is so common, so widely used in every situation, there are multiple ways to say it:

shikata ga arimasen (polite)

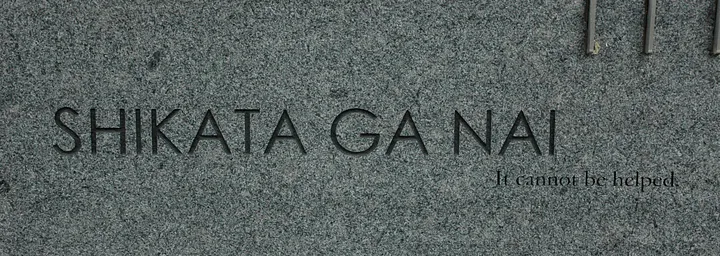

shikata ga nai (informal)

shō ga nai (cas ual)

shānai (Kansai-ben)

But what does this ubiquitous expression mean?

Shikata ga nai is hard to translate into English since there’s nothing similar in our language.

The closest equivalent is actually from French: c’est la vie. We use the French because we couldn’t come up with an English expression of our own. The French translates literally to “That’s life…”

The Japanese expression is formed from shikata (仕方) meaning method or way, and nai (無い) (arimasen) meaning its absence. So shikata ga nai literally means there is no way to do something, i.e. it’s hopeless, it can’t be helped, there’s no choice.

Typical situations where you’ll hear the expression:

Frustrated by Japanese politics: shikata ga arimasen

Your company instituted a stupid policy: shikata ga nai

Going crazy filling out paperwork: shō ga nai

Hanshin lost another baseball game: shānai na~

If that sounds like an expression of hopelessness, it isn’t, not always.

Instead, it means that life is what it is, so there’s no point in complaining, we have to deal with it. It ties closely to another key Japanese trait: gaman (我慢) — endurance and perseverance.

I liken the attitude of shikata ga nai to the Serenity Prayer:

The expression shikata ga nai embodies this serenity and wisdom. Where Americans like me will whine about every problem, beg for exceptions to rules we don’t like, make loud complaints on Twitter about everything wrong with the world, and demand our elected representatives do something about it, my (Japanese) wife will mutter shō ga nai and maybe a few aho sugiru’s before setting out to deal with whatever is thrown at her.

I’m convinced the long lifetimes of Japanese people have nothing to do with ikigai or an Okinawan diet, but the serenity that comes from embracing the philosophy of shikata ga nai.

Shikata ga nai is an attitude of resiliency and endurance. It is what it is, so deal with it. A decision has been made, and whether we like it or not, it’s time to stop arguing and start moving forward.

- Earthquake destroy a major section of the country? Shikata ga nai. We have to rebuild.

- Energy prices skyrocketing due to the war in Ukraine? Shikata ga nai. Put on sweaters and lower the thermostat.

- The country needs a fast rail line to reach more communities? Shikata ga nai. We have to move out of the way.

But this willingness to accept the world as it is instead of the way we want it to be can be a double-edged sword.

Some things that need to be changed such as Japanese politics and Japanese company’s treatment of women, don’t get changed. Too many people say shikata ga nai — it sucks, but too bad, it is what it is, turning its immutability into a self-fulfilling fact.

In the US, there is no concept of shikata ga nai. Until the plus-sized lady sings and the lights go off, there’s still a chance to win. If you don’t fight to the death you’re a loser, and there’s nothing worse than that.

But will my fighting and complaining actually accomplish anything? Occasional, yes. Seats have been upgraded on airlines when I’ve complained about crappy service, broken products have been replaced when I made a big enough stink.

But usually not, especially not in politics or anything that really matters. I fight for change, protest for change, donate money for change. Nothing changes. Except my rising blood pressure.

My wife laughs at me. Shō ga nai, she tells me and goes back to her work. I need to find the serenity to accept the things I don’t like if I want to live a long and contented life like her.