Why are people curious?

What are the benefits of a curious mind?

In a time of uncertainty about the future, curiosity is a critical skill for finding a way forward. In terms of our evolution, it makes sense for humans to be curious about the world around them. In the words of brilliant physicist Albert Einstein, “I have no special talent – I am only passionately curious.”

Curiosity helps us learn better, the research suggests. Specifically, we’re better at learning things we’re curious about.

Professor Celeste Kidd’s research found we’re most curious when we feel uncertain about something. “Uncertainty indicates that there’s valuable knowledge available,” she says. “By contrast, certainty indicates you know everything there is to know so there’s no point in continuing to be curious because there’s nothing further to be gleaned.” This is sensible, she says, because it guides us towards what is most useful for us to learn. In these rather uncertain times, curiosity can help us to focus on the most pressing issue. This could explain the growing interest in sustainability, the circular economy and ethical data use.

What are learning theories? 🔗

Since Plato, many theorists have emerged, all with their different take on how students learn. Learning theories are a set of principles that explain how best a student can acquire, retain and recall new information.

Learning theories in education 🔗

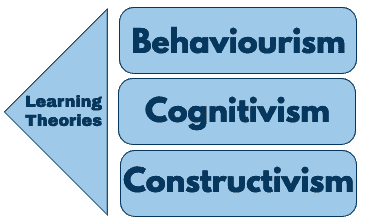

There are 3 main schema’s of learning theories; Behaviorism, Cognitivism and Constructivism. We will briefly discuss each one and an explanation of the most influential learning theories; from Vygotsky to Piaget and Bloom to Maslow and Bruner.

Despite the fact there are so many educational theorists, there are three labels that they all fall under. Behaviorism, Cognitivism and Constructivism.

Behaviorism 🔗

Behaviorism involves repeated actions, verbal reinforcement and incentives to take part. It is great for establishing rules, especially for behavior management. Behaviorism is based on the idea that knowledge is independent and on the exterior of the learner. In a behaviorist’s mind, the learner is a blank slate that should be provided with the information to be learned.

Through this interaction, new associations are made and thus learning occurs. Learning is achieved when the provided stimulus changes behavior. A non-educational example of this is the work done by Pavlov.

Cognitivism 🔗

In contrast to behaviorism, cognitivism focuses on the idea that students process information they receive rather than just responding to a stimulus, as with behaviorism. There is still a behavior change evident, but this is in response to thinking and processing information.

Cognitive theories were developed in the early 1900s in Germany from Gestalt psychology by Wolfgang Kohler. In English, Gestalt roughly translates to the organisation of something as a whole, that is viewed as more than the sum of its individual parts.

Cognitivism has given rise to many evidence based education theories, including cognitive load theory, schema theory and dual coding theory as well as being the basis for retrieval practice.

In cognitivism theory, learning occurs when the student reorganises information, either by finding new explanations or adapting old ones.

This is viewed as a change in knowledge and is stored in the memory rather than just being viewed as a change in behavior. Cognitive learning theories are mainly attributed to Jean Piaget.

Constructivism 🔗

Constructivism is based on the premise that we construct learning new ideas based on our own prior knowledge and experiences. Learning, therefore, is unique to the individual learner. Students adapt their models of understanding either by reflecting on prior theories or resolving misconceptions. Students need to have a prior base of knowledge for constructivist approaches to be effective. Bruner’s spiral curriculum is a great example of constructivism in action.

As students are constructing their own knowledge base, outcomes cannot always be anticipated, therefore, the teacher should check and challenge misconceptions that may have arisen. When consistent outcomes are required, a constructivist approach may not be the ideal theory to use.

Domains of learning 🔗

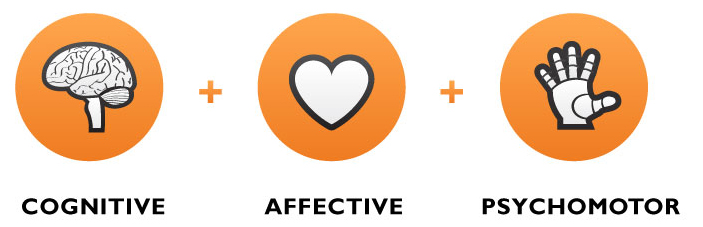

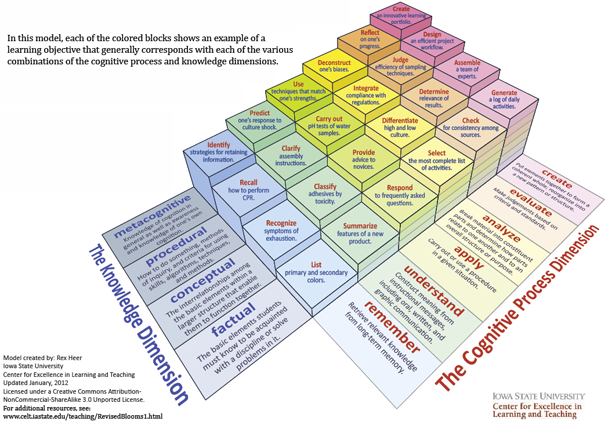

Bloom and his collaborators have provided a framework upon which teachers can build lessons and curricula, students must master one level before building to mastery of subsequent levels.

Bloom’s taxonomy is not a simple classification scheme – it is a hierarchical arrangement of cognitive processes that lend themselves perfectly to teachers planning lessons and allowing students to build upon their prior understanding. It has been developed precisely to help teachers formulate learning outcomes and as a guide to devising assessment criteria tailored to the type of cognitive domains and mental and companion skills being assessed.

If teachers involve the students themselves in this process, encouraging them to self-assess by comparing expected and achieved outcomes, it will also contribute to the development of learning motivation. Student self-assessment is a brilliant tool for developing students’ responsibility for their progress and success in learning. After reviewing the work of Bloom and his associates, it is evident that his contribution to the planning, organization and structuring of the educational process is remarkable.

What Are the three domains of Bloom’s Taxonomy? 🔗

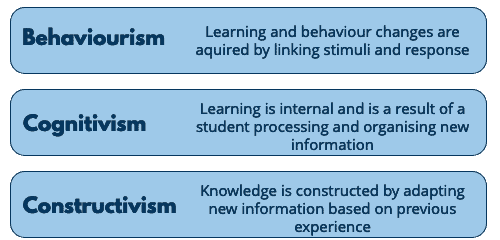

With his colleagues David Krathwohl and Anne Harrow, Benjamin Bloom proposed three domains of learning.

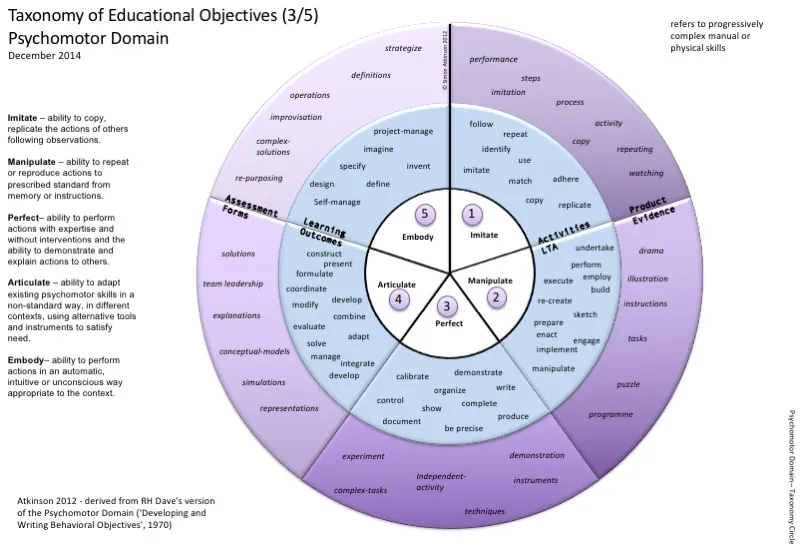

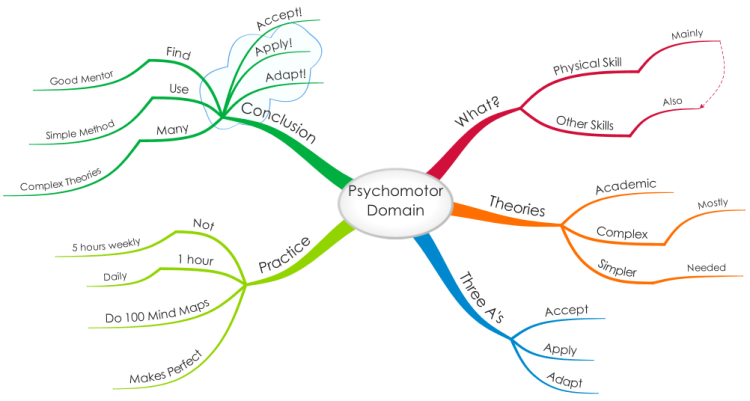

The three domains that form Bloom’s taxonomy are; the cognitive domain (knowledge), the affective domain (attitudes, values, and interests) and the psychomotor domain (skills).

Cognitive domain 🔗

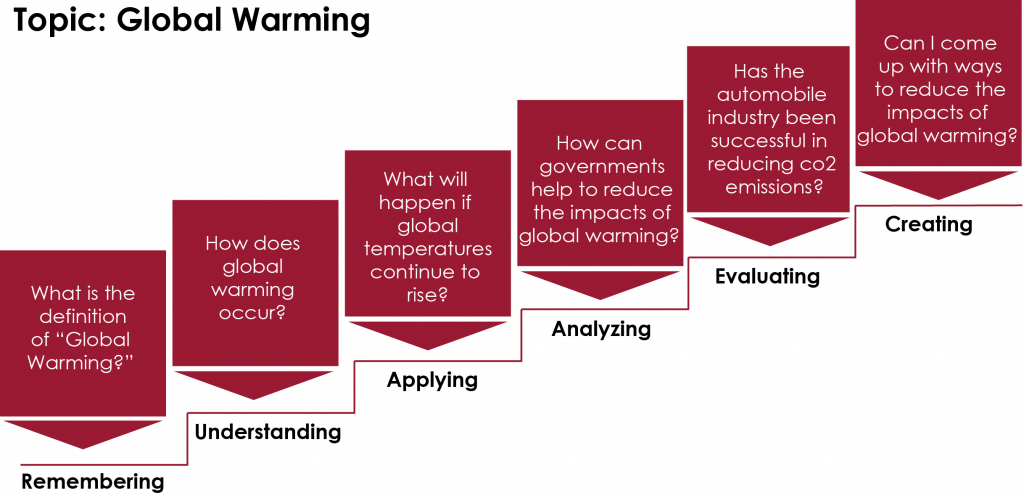

The levels of Bloom’s taxonomy build upon each other. While you need to be able to remember key concepts, your courses will spend more time developing your ability to apply, analyze, evaluate, and create using this knowledge. As you encounter new concepts, you will want to use critical questioning to understand the concepts at all levels, moving from surface to deeper knowledge. The chart below includes some questions that might be relevant at each level.

🎥 What is Bloom's Digital Taxonomy? | Video (4:51 minutes)

Affective domain 🔗

Psychomotor domain 🔗

Identifying skills for self-directed learning 🔗

Many students have experience in teacher-directed classrooms. In these classrooms, the teacher is the central figure, and the students take direction about what to learn directly from the instructor. In these environments, students might spend time taking notes on an instructor’s lecture, and might focus much of their learning time on memorizing concepts in preparation for recalling them on an exam.

Online courses are different. The instructor is no longer the central figure in the learning environment. You, the student, become the central actor in your own learning journey. As you undertake this journey, you are supported by your community of fellow students. Your instructor serves as your guide, using their knowledge and experience to direct you to learning experiences that will lead you to your learning goals.

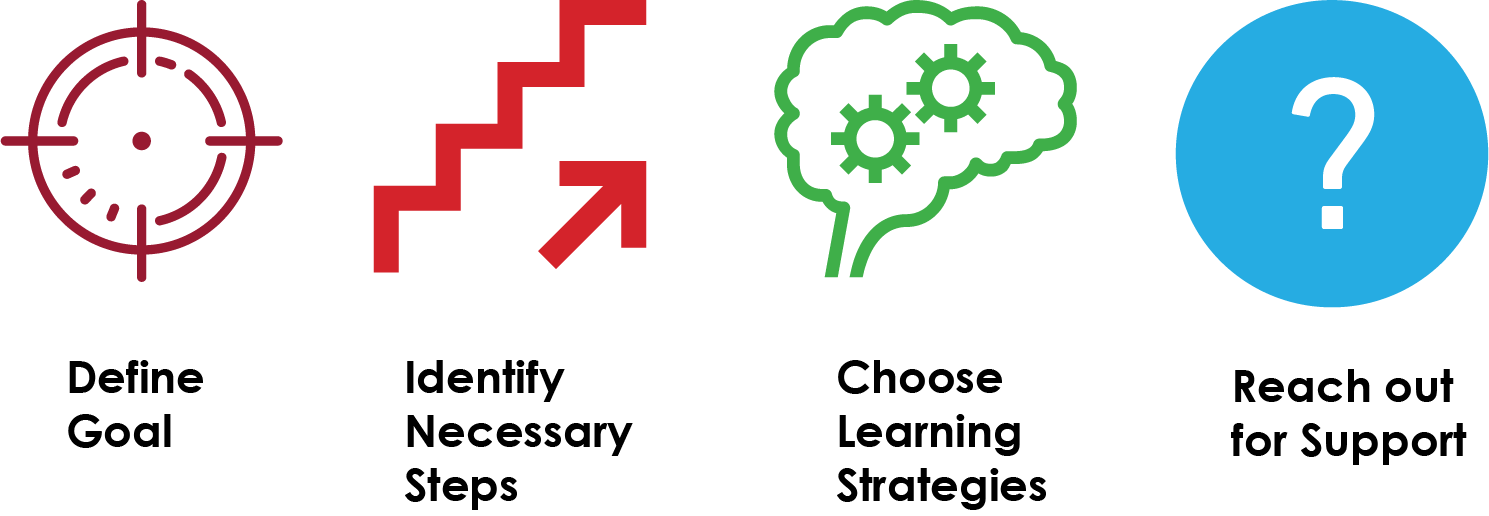

Independent learning requires the following skills:

- Defining your learning goal for your program, each course, and each assignment you complete.

- Identifying the steps you must take to move towards your goal. What content do you need to know? How will you learn it?

- Choose strategies that will support your own learning.

- Reach out for the support you need from your instructor, classmates, and university support services.

Apply the plan-monitor-evaluate model for assessing your learning progress 🔗

What is Metacognition? 🔗

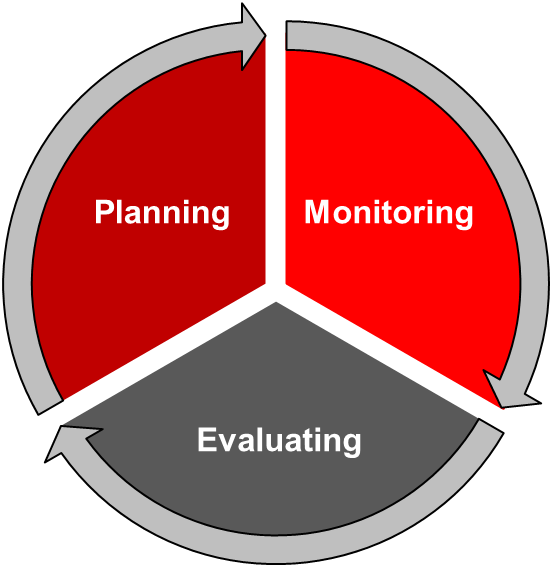

Have you ever wondered what the most successful students do differently from other students? Students who have developed effective ways of learning have mastered a skill called metacognition. In simple terms, metacognition is understanding your own thinking and learning processes. In other words, it is “thinking about your thinking”. Metacognitive skills include planning your learning, monitoring whether your current learning strategies are successful, and evaluating results of your learning. Improving your metacognitive skills is associated with increased success in all of your academic life. To learn more about how metacognition applies to student life, watch the video below.

Learning Choices: Videos and Text

At several points in a textbook, you will have the opportunity to learn key skills by watching a short video. If you prefer reading to watching videos, you can find a video transcript for each video. Skip the video to read if this is your learning preference.How do you gain the skill of metacognition? One way to think about developing metacognition is gaining the ability to plan, monitor, and evaluate your learning.

Planning involves two key tasks: deciding what you need to learn, and then deciding how you are going to learn that material.

Monitoring requires you to ask “how am I doing at learning this?”. In monitoring, you are constantly tracking what you have learned, what you don’t yet know, and whether your study strategies are helping you to learn effectively.

Evaluation involves reflection on how well you met your Learning Objectives after completing a unit of study, or receiving feedback (such as a test or assignment).

Key Questions to Improve Your Learning 🔗

At each stage in the learning cycle, there are key questions that you will ask yourself to support your learning process. In the chart below, you will identify the key question for each stage in the cycle, along with the other questions you will want to consider.

Reflect 🔗

One key metacognitive skill is being able assess what you already know about a course topic, and to identify what you would like to learn through your reading, discussions, assignments and other class activities.

Using critical questioning to support your learning 🔗

One method for creating study questions or planning active learning activities is to move step-by-step through each level of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Begin with a few questions at the Remembering level. If you don’t yet know the technical language of the subject and what it means, it will be difficult for you to apply, evaluate, analyze, or be creative. Then, go deeper into your subject as you move through the levels. Learning at university requires you to learn the basics of your discipline by remembering and understanding; however, you will spend much more of your time applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating.

Here is an example of what this might look like. What questions can you create for your topic?

Create study questions using bloom’s cognitive taxonomy 🔗

Pick a subject area in which you are working. For each level of Bloom’s Taxonomy on this page:

- Develop a question and answer it to show that you can think about the material at that level. Use the example questions on the handout above as a guide.

- Think about how your questions would allow you to assess how much you know and what level you are working at.

Defining your learning community 🔗

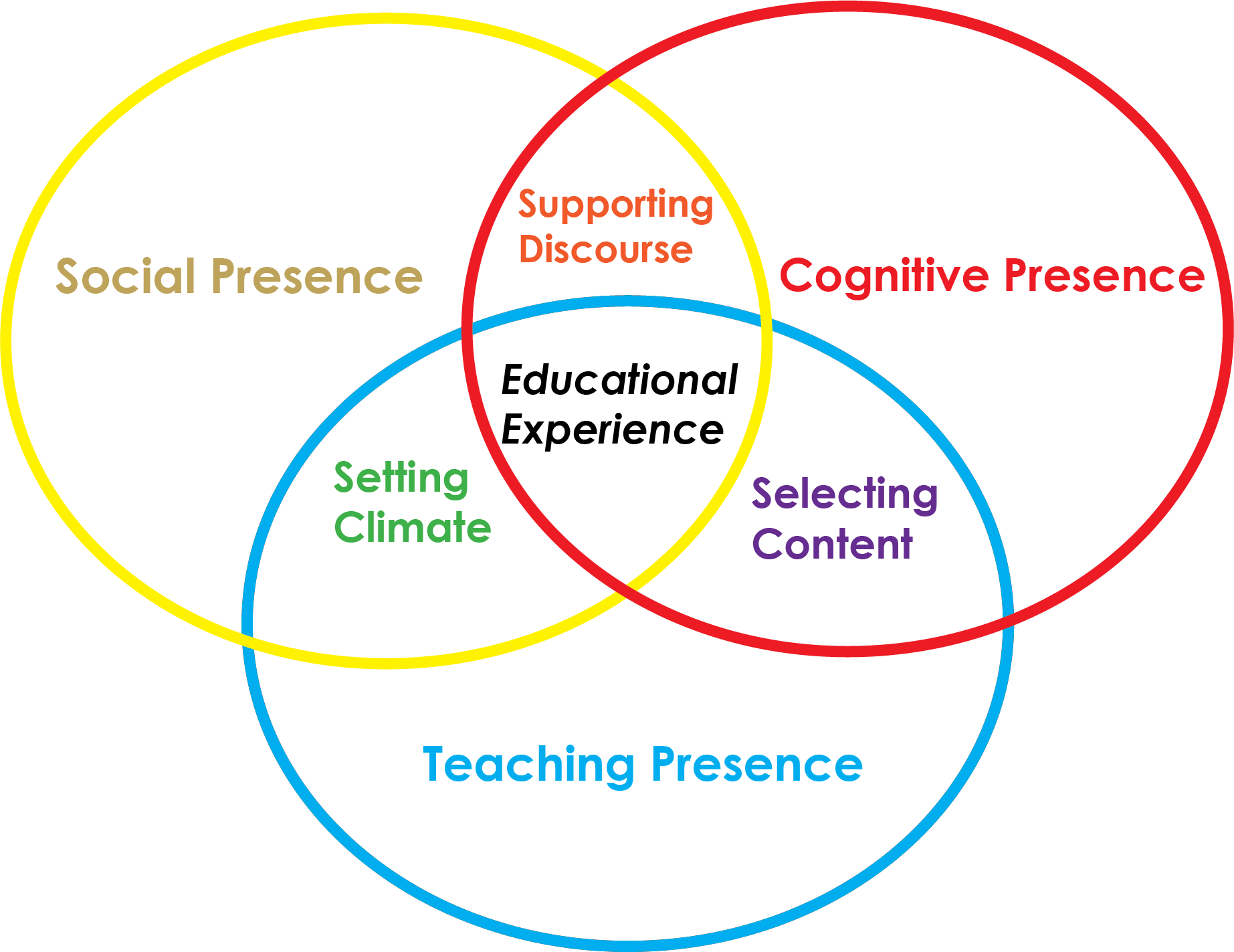

When you join an online course, you become part of what is known as a Community of Inquiry. In the Community of Inquiry, you will have an Instructor, content to process, and a learning community in which to grow.

This is a learning community that fosters your learning (cognitive growth), in a way that allows you to apply new insights to your life and work. Within a Community of Inquiry, learners have two key roles:

- Maintaining a cognitive presence in the community. This requires a continual process of critical thinking.

- Developing a social presence in the learning community. This involves creating the open and mutual relationships that allow for learning and collaboration to occur.

Cognitive presence and critical thinking 🔗

How does learning happen? Is it the result of reading, memorizing, and taking exams? While many learning experiences have these components, the best kind of learning involves constructing new knowledge in a learning community. This requires interacting with new information (for example, from readings, discussions, videos, and lectures). You may receive this information with instructors, from fellow students, or you may search it out to solve questions or problems. Then, together with your learning community, you make connections between this new knowledge and your prior experiences. You also determine how this new knowledge will shape your professional practice.

The Community of Inquiry supports this process through the exchange of ideas, supporting one another exploring connections, and challenging ways of thinking through thoughtful questioning.

Social presence 🔗

If learning occurs in a collaborative community, how does this take place online? Maintaining a social presence in an online environment involves allowing for open communication. Social presence allows you to risk expressing your ideas online, based on the knowledge that your classmates will be respectful and supportive. All members of the community commit to supporting each other in their learning. Though it may be difficult to express some nuances and emotions online, using emoticons can help.

Group work is also a key part of the Community of Inquiry experience. The best online learning experiences happen when you are able to form connections within a team as you work towards your learning goals. The next sections of this module provide strategies for developing your learning community in the context of group work and team development.

Understanding the principles of effective teamwork 🔗

Now that you have identified what you hope to achieve through teamwork in your learning community, consider how you will form effective teams.

Five basic elements of effective teams 🔗

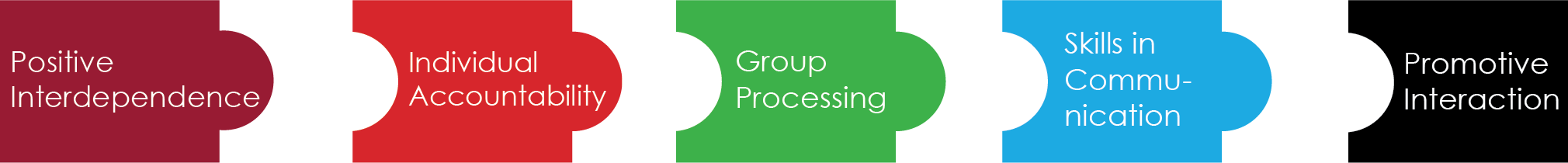

Effective teams share five key characteristics:

| Positive Interdependence | Members believe they are linked together; they cannot succeed unless the other members of the group succeed (and vice versa). They sink or swim together. |

| Individual Accountability | The performance of each individual member is assessed and the results given back to the group and the individual. |

| Group Processing | At the end of its working period, the group processes its functioning by answering two questions: ⚪ What did each member do that was helpful for the group? ⚪ What can each member do to make the group work better? |

| Skills in Communication | Necessary for effective group functioning. Members must have — and use — the needed leadership, decision-making, trust-building, communication, and conflict-management skills. |

| Promotive Interaction | Members help, assist, encourage, and support each other’s efforts to learn. |

Planning for successful teamwork 🔗

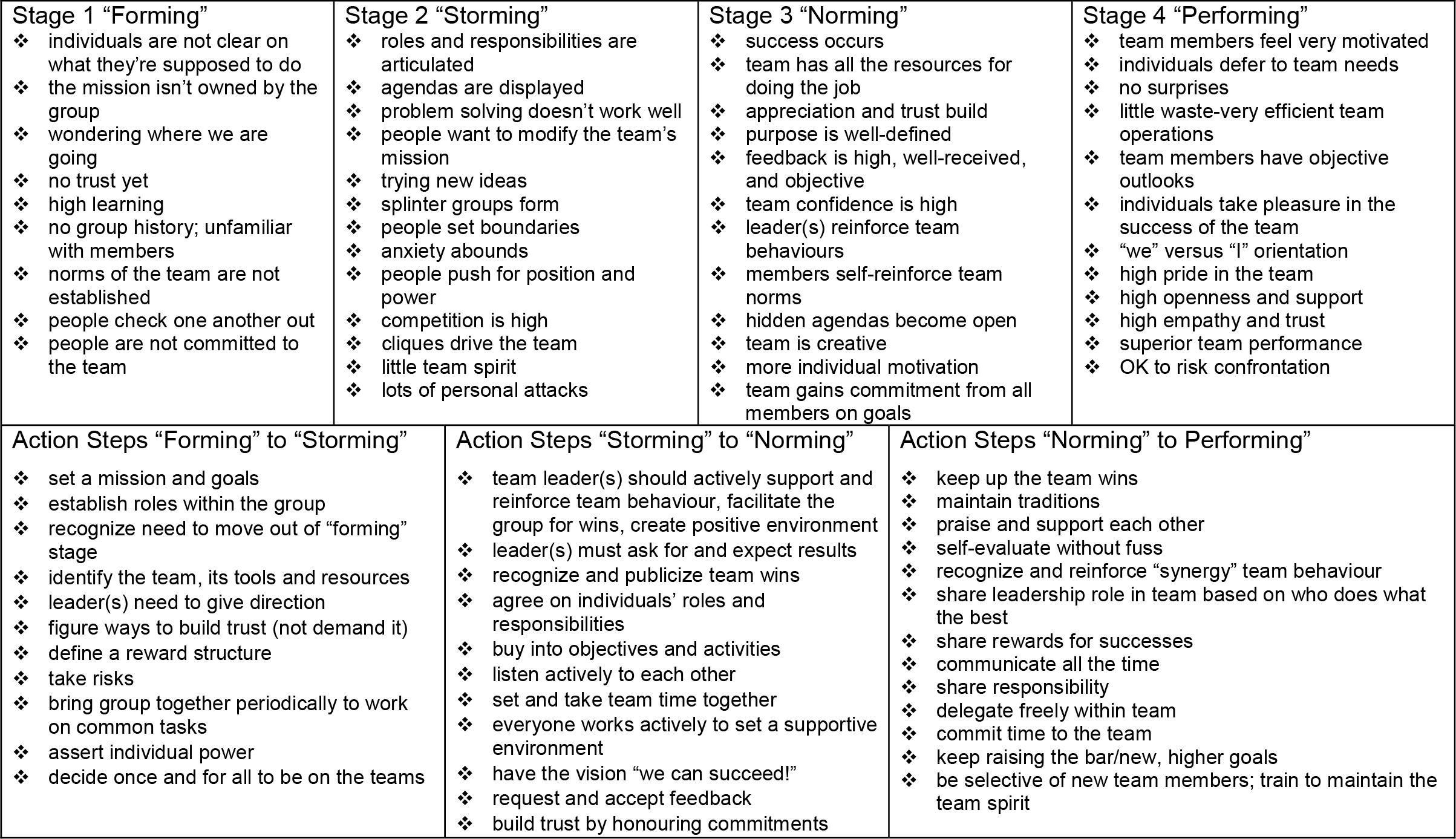

Tuckman suggested that teams move through stages in their life cycle: forming, storming, norming, and performing. At each stage, the group will work through a series of interpersonal tasks, as well as a series of project-related tasks.

In the first section of this module, you explored the components of a Community of Inquiry. Both cognitive presence and social presence are required in the online learning community. Tuckman’s model of team development also indicates that both components are needed. In a class-based team, it may be easy to focus only on the cognitive output of the group — the creation of the project, paper, or presentation. However, as you can observe from Tuckman’s model, a well-functioning team requires its members to exhibit social presence throughout, communicating well in interpersonal interactions.

In the days ahead, you will likely find yourself on a newly forming team in an online environment. Consider the strategies you plan to use to demonstrate social presence and form a strong interpersonal foundation for your newly forming team.

Progressing through the stages of team development 🔗

As your group moves through these stages, stay aware of the patterns that tend to occur at each stage. For example, many teams falsely assume that their group cannot function when they find themselves at the storming stage. However, this stage is a normal part of team development, like the others. The infographic below indicates what steps you and your group members can take together to move to the next stage in your work together. Ultimately, you want to achieve a performing team that supports your learning in community.

Now that you have reviewed the ways that a team can move on in their development, apply your knowledge to team dilemmas in the quiz below. When you have finished the quiz, go to the next chapter to move on in the workshop.

Make commitments that support teamwork 🔗

Review some key concepts about becoming an effective team, presented within the infographic below.

Becoming a team 🔗

A Team is two or more people; working together; on a Common Goal (or goals). Groups become Teams if the common goals are clear and attention is paid to both interpersonal and task functions.

The Team must decide how to communicate effectively (interpersonal) 🔗

Each Team must set up their own guidelines for good communication and a Team Charter. Through discussion and negotiation the members choose the items that are most important for their clear communication as a Team. These often include commitment to:

- Respect and Listen to others

- Not blame (work hard on the problem, not on the person)

- Group members and Project process

- Supportive and Constructive Feedback

- Agreed upon Goals and Clear Timelines

- Positive interdependence (sink or swim together)

- Individual Accountability (say what you will do and do it)

- Analysis of work done and Planning for next steps

- Process for conflict and Problem Management

The Team must decide what is important and measure this (task) 🔗

Early in the formation of the group, the members must decide what will be measured in the process. These items are generally critical to success and for the group to become an Effective Team. A team that has succeeded shares the following characteristics. Its members:

- Came prepared

- Offered ideas and suggestions, Provided information

- Asked for clarification/feedback

- Identified resources

- Solicited others’ participation

- Kept group on task

- Was easy to work with

- Prepared materials

- Made presentation

- Participated in discussions

- Managed group conflict

The Team must acknowledge success and aim for improvement 🔗

What have we done (individually and collectively) to meet our goals and keep the Team Charter?

How can we do better for next time? (Next steps)

The Team celebrates! 🔗

Celebrate what you have accomplished and then refocus your efforts for greater success!

Framework for working together 🔗

Core Values 🔗

Your personal beliefs are the core values that affect and drive how you look at the world, your behaviour in the world and your interaction with others. They are how you do “business” with the rest of the world. In other words, they are the basis for everything that you are and do. These beliefs about appropriate behaviours, attitudes and strategies also guide every working group and need to be explicit and understood.

Mandate 🔗

It is useful to know what you are expected to do in a group situation. This is often delivered or requested from an administrative or political level and appears in the form of a “job description”. The group which is mandated may not be able to effect the general outline of the mandate. The context in which the group operates has critical effects on what can be done.

Identifying a mission statement 🔗

A mission statement embodies the group’s current purpose and intent and answers (within the mandate of the group) questions such as: What are we about? Why are we working together? What do we want to achieve? It describes the business that you are in. This may be a statement developed by the whole organization or it may be more localized in a department, program, class, work group or individually. It gives direction to actions. Without knowing your mission, you may not be able to get started.

Developing shared vision 🔗

Vision is a future oriented statement of a group’s purpose in a task, project or work team. Having the members shared a vision that aligns with their personal values and aspirations is a solid basis for production. Time spent at the beginning in dreaming and discussing what the final result will be is time well spent. If it is not possible to have a shared vision of the end product and the goals and milestones that must be reached then the team may also have difficulty identifying whether they have accomplished their purpose.

Sometimes, when the project is open ended or ongoing, the final product cannot be totally “visioned” at the beginning. A shared vision will then be one that all of the team members agree are the elements of where they want to get at this time and the direction that they will start moving towards to achieve these elements.

Visions should be revisited and refined over time. If the team is not heading in the same direction, then it may not get anywhere.

Determining appropriate goals 🔗

What are the individual tasks and goals that will build to making your vision manifest? Goals lead towards the realization of the vision. It is important to develop appropriate goals, make them explicit and share an understanding of each one.

Goals have:

- Targets – where we expect to get to realistically balanced with time and resources.

- Objectives – identifiable, measurable and achievable steps.

- Tasks – ways of reaching the objectives.

- Indicators – ways of measuring progress.

- Like our vision statement, goals need to be realigned with reality on a regular basis. Evaluation and adjustment drive this process.

Improving continuously 🔗

Knowing where you are going and how you intend to get there is a good start. The final step is continuous improvement. Planning, implementation, and verification are tools for analysis and change as the process unfolds. Improvement is continual but the steps are small. Pick changes that can be made now that will have a positive effect – 1% is enough each time.

Manage daily tasks 🔗

Now that you can see the big picture of your learning schedule and weekly priorities, the next step is to create a daily to-do list to prioritize your tasks. The video below introduces you to some principles for creating daily task lists. When you are finished, click the Next arrow to choose strategies for managing your tasks.

Choosing a daily task management system 🔗

Some students prefer paper-based task management systems, while others prefer to use technology to manage daily tasks. Consider the following advantages and disadvantages of systems you might choose.

Reflection and Action 🔗

Consider what kind of task management system will help you most in your current study program:

Using small blocks of time 🔗

Through using smaller blocks of time you can cover material in chunks (more on the next page) and not have to worry about the larger whole. A mistake that many people make is that they try to cram information into their minds in one large session. This isn’t a successful strategy for most students.

Look for smaller blocks of time to study. If you are a public transit user, you can likely spend 20 minutes on your bus ride to read or review for your upcoming class or exam. You could even listen to an audio recording of your notes. In the evening, instead of watching three episodes of your favourite TV show, you could watch one and spend the remaining time preparing for your studies. Going out to eat often? Consider making something simple at home that you could put in the oven to cook without needing tending to; that time could be used doing some work for class and still leave you time for other activities once dinner is done.

Making time for your studies can be overwhelming. The following video introduces you to ways to use smaller blocks of time to get your tasks done, while not using up numerous hours at once.

One trick to balancing work and study is taking advantage of small blocks of time to get things done.

Consider the small blocks of time in your schedule, and identify strategies to increase your productivity during these moments in your day.

Often, we think we need to have a lot of time available for study, or we think that we can only study at home or in the library. By adjusting your thinking, you’ll be able to open up additional productive learning time.

- Do you commute by transit? Though it wouldn’t be ideal to try to master detailed or complicated reading material on the bus, perhaps you can do some initial scanning or skimming while in transit, to prepare yourself for class or deeper reading later.

- Consider creating flash cards for material that you need to learn. You can take a set of flash cards with you and work whenever a few minutes become available. If you use one of the many flash card or self-testing apps available on your phone, you’ll be able to easily pull out your phone and make use of those small blocks of time.

- Self-testing is one of the most effective ways to learn. Create a list of study questions for your course. Pull out the list when you have time available, and review a few questions. Keep track of those you answer correctly, and those you need to study more.

- Does your course include access to online videos that explain and review key concepts? Watch a video or two to review, or to improve your understanding of a key course idea.

- Some courses also include access to online self-study questions. Try answering a few review questions in your spare moments. These online quizzes usually provide immediate feedback on what you understand, and what you should study further.

- Do you like to learn by listening? Make an audio recording of the important points you want to remember, and listen while you commute or exercise. Maybe audio books are for you – are any of your course materials available in this format?

Assessing the place of reading in your learning journey 🔗

Reading and the online learning journey

Online learning typically requires you to interact with a larger amount of written material than traditional in-class courses. This can benefit your growth as a lifelong learner by developing your skills in selecting relevant reading material, approaching it purposefully, and managing the information you read.

Consider the following principles as a guide as you approach reading:

- Not all reading material requires equal time or attention. Unlike a novel, where you give most pages equal time in order to understand the story, much of your professional reading is focused on finding and using relevant information. This means that you may not read every word in available readings. Some information may require a close and careful reading, while other information may be skimmed to find key points.

- Before you begin reading, identify your purpose for reading. What do you need to learn from this reading? This will determine how you approach the reading material.

- Use questions to guide your reading. In the next sections of this module, you will learn a strategy called SQ3R that can guide you through the process of using questions to guide your reading.

- Develop a system for identifying important information and taking notes. You have already explored systems for online information management. Consider how you will mark key learnings in the texts that you read, and organize this information in a form where you can easily access it again.

The SQ3R method for strategic reading 🔗

In this chapter, you will watch a short video that describes a method called SQ3R that provides a way to read efficiently and purposefully. After the video, you will complete a quiz that tests your knowledge of the content you learned. If you prefer reading to watching a video, scroll below the video to find a transcript.

Applying the SQ3R method 🔗

Now that you are familiar with the steps of the SQ3R Method, you may want to apply them to a text you are reading this week. To see how the steps are applied to an actual reading activity, watch the video below. At several points in the video, you will have the opportunity to pause and try the steps in the method. When you are finished the video or reading, go to the next chapter to move on in the workshop.

Apply it! 🔗

Commit to trying the SQ3R method once this week as you complete your course readings. As you do, consider the following questions:

- How does the SQ3R method change how you approach your reading?

- How will you adapt and personalize this process to your own learning strengths and the specific requirements of your courses?

How to read journal articles strategically 🔗

Throughout your academic career, you will read a variety of journal articles as you complete coursework and conduct research for assignments. Journal articles may seem daunting, but by understanding how journal articles are organized and written, you will be able to choose relevant articles and find the information you need.

Parts of a journal article 🔗

| Abstract and Keywords | This is a concise summary of the article. Read this first to decide if the article is relevant to your current research topic. Below the abstract you will find 4~5 keywords. These indicate the subject area of the article. |

| Literature Review | Most articles will have a literature review early in the paper. This summarizes the past research done on the topic. Note that this is not a discussion of the research in the current article. However, the literature review may point you to other material relevant to your project. |

| Research Methodology | This section describes the way in which the research was conducted. Who are the participants? Is the study qualitative or quantitative? How was the data gathered? Where was the study conducted? |

| Results | This section discusses the findings of the study in detail. It often includes statistical information, charts and graphs. |

| Discussion | In this section, the researchers discuss the significance of the results. What do the results mean? Are they significant? What are the implications of what was found? The authors might also indicate areas for further study. |

| References | Skim the reference list. This may lead you to other key articles that are related to your topic. |

How to approach journal articles 🔗

- Begin by reading the abstract and keywords. Decide if this article relates to your current research project. If the article does not fit well with your research, stop reading.

- If the article seems relevant, scan the article briefly. Look at the headings, as well as terms in bold and italics. Also, look at charts and graphs.

- Before you begin reading the article, note the bibliographic information. You will need this for your Works Cited or References page.

- Now, read the discussion section closely. This is key to understanding the article well.

- On a separate sheet of paper, create questions that you will answer by reading the article. Include questions such as: “From what you know, does this author agree with other researchers and what you understand about the topic? Does this article support or contradict your thesis?”

- Read the article purposefully, answering your questions. Do not be afraid to change your questions as you read and discover more.

- When you find the answers to your questions, write them down, along with the page number where you found the information. You will need the page numbers to properly cite your sources when you write.

As you learn to approach journal articles systematically, you will become skilled at extracting important information as you read.

How to take effective notes on online readings 🔗

Why take notes on online content? After all, you can easily search for it and read it again. However, re-reading is not always the most effective use of time. Taking good notes helps you to quickly review the key points in the material that you have read.

Taking notes is also an effective learning strategy. Intentionally annotating the texts that you read requires you to critically engage with the material. You are doing the work of identifying the important content, and considering its implications for your course and your professional practice. This practice facilitates deep learning, and ensures that you remember key material.

Choose the note taking method that is most effective for you. You may prefer traditional notebooks. Many readers underline, highlight, and put key notes in the margins of their books. You may prefer to create typewritten notes, and to store these notes in using your electronic notebook / information management system.

Another tool for engaging with digital texts is Hypothes.is.

🎥 Active Reading with Hypothes.is | Video (4:43 minutes)

Padagogy Wheel 🔗

References 🔗

- Benjamin Samuel Bloom, “Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals”, published by Longman Group, June 1969. ISBN-10: 0679302115. ISBN-13: 978-0679302117.

- Lorin W. Anderson & David Reading Krathwohl, “A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Abridged Edition”, published by Pearson Education, December 2000. ISBN-10: 080131903X. ISBN-13: 978-0801319037.

- Elliot Wayne Eisne, “Benjamin Bloom: 1913-1999”, published by UNESCO: International Bureau of Education, September 2000. Retrieved 22 September 2016, from http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/archive/Publications/thinkerspdf/bloome.pdf.

- Chick, N. (2017). Metacognition. Retrieved August 31, 2017, from https://wp0.vanderbilt.edu/cft/guides-sub-pages/metacognition/

- Tanner, K. D. (2012). Promoting student metacognition. Cell Biology Education, 11(2), 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.12-03-0033

- Athabasca University. (n.d.). Community of inquiry coding template. Retrieved from http://cde.athabascau.ca/coi_site/documents/Coding Template.pdf; Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (1999). Critical Inquiry in a Text-Based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2–3), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

- Johnson, D., T. Johnson, R., & Smith, K. (1998). Active Learning: Cooperation in the College Classroom (Vol. 47). https://doi.org/10.5926/arepj1962.47.0_29

- Tuckman, B.W. (1965) ‘Developmental sequence in small groups’, Psychological Bulletin, 63, 384-399. Reprinted in Group Facilitation: A Research and Applications Journal ,Number 3, Spring 2001

- https://www.celt.iastate.edu/teaching/effective-teaching-practices/revised-blooms-taxonomy/

- https://artsphere.org/blog/why-creating-is-so-important-in-education-compare-the-revised-and-original-blooms-taxonomy-and-related-verbs-to-help-parents-become-teachers/

- https://designingoutcomes.com

- https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/learningtolearnonlineatfanshawe/

- https://www.educationcorner.com/learning-theories-in-education/

- https://www.educationcorner.com/blooms-taxonomy/

- https://www.teachthought.com/critical-thinking/blooms-digital-taxonomy-verbs/

- https://lynnleasephd.com/2018/08/23/krathwohl-and-blooms-affective-taxonomy/

- https://sijen.com/2018/09/02/the-role-of-psychomotor-skills-in-higher-education/

- https://www.usingmindmaps.com/study-skills-bloom-psychomotor-domain.html

- https://ivanteh-runningman.blogspot.com/2016/09/blooms-taxonomy.html

- https://coi.athabascau.ca/coi-model/